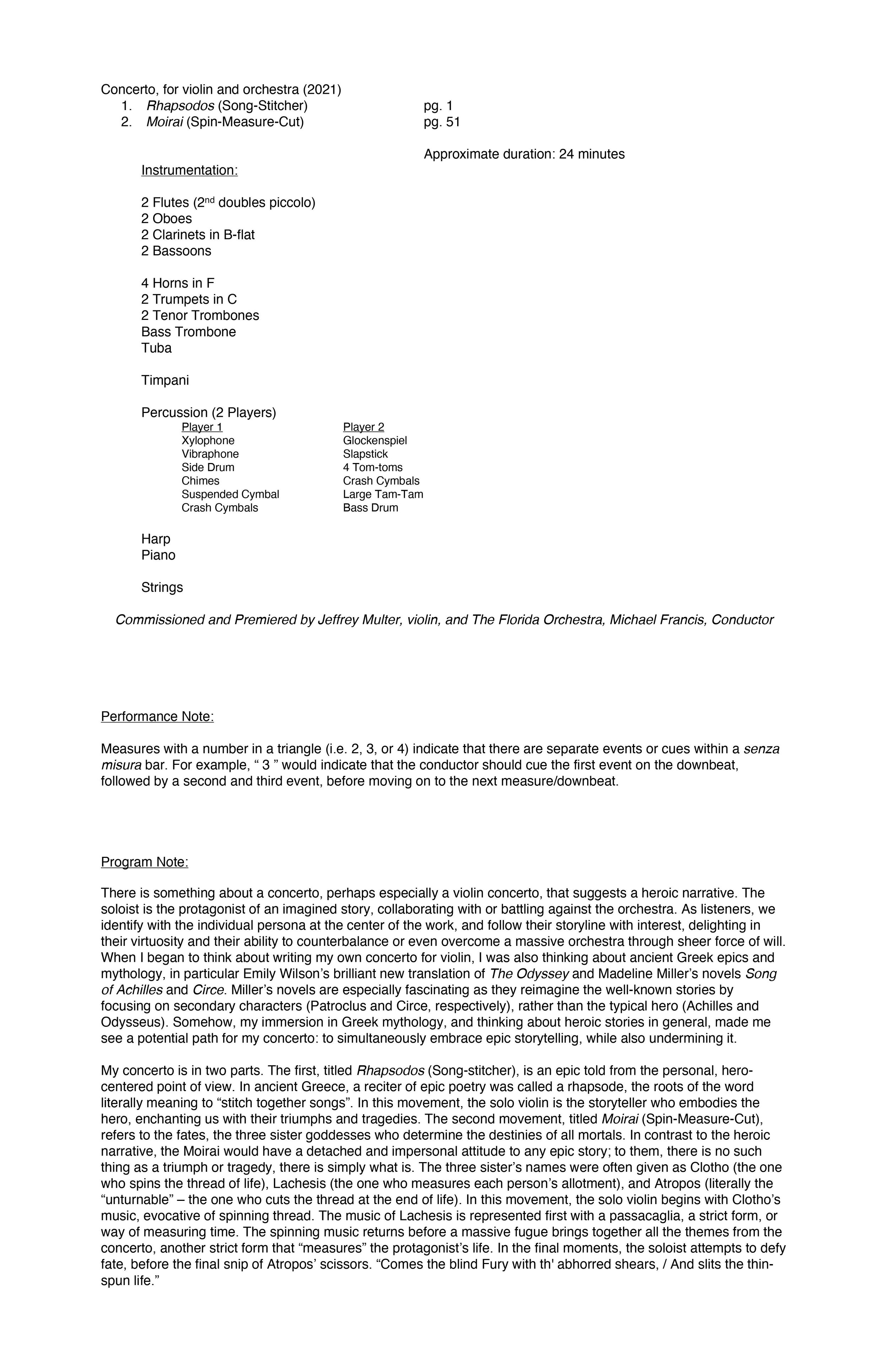

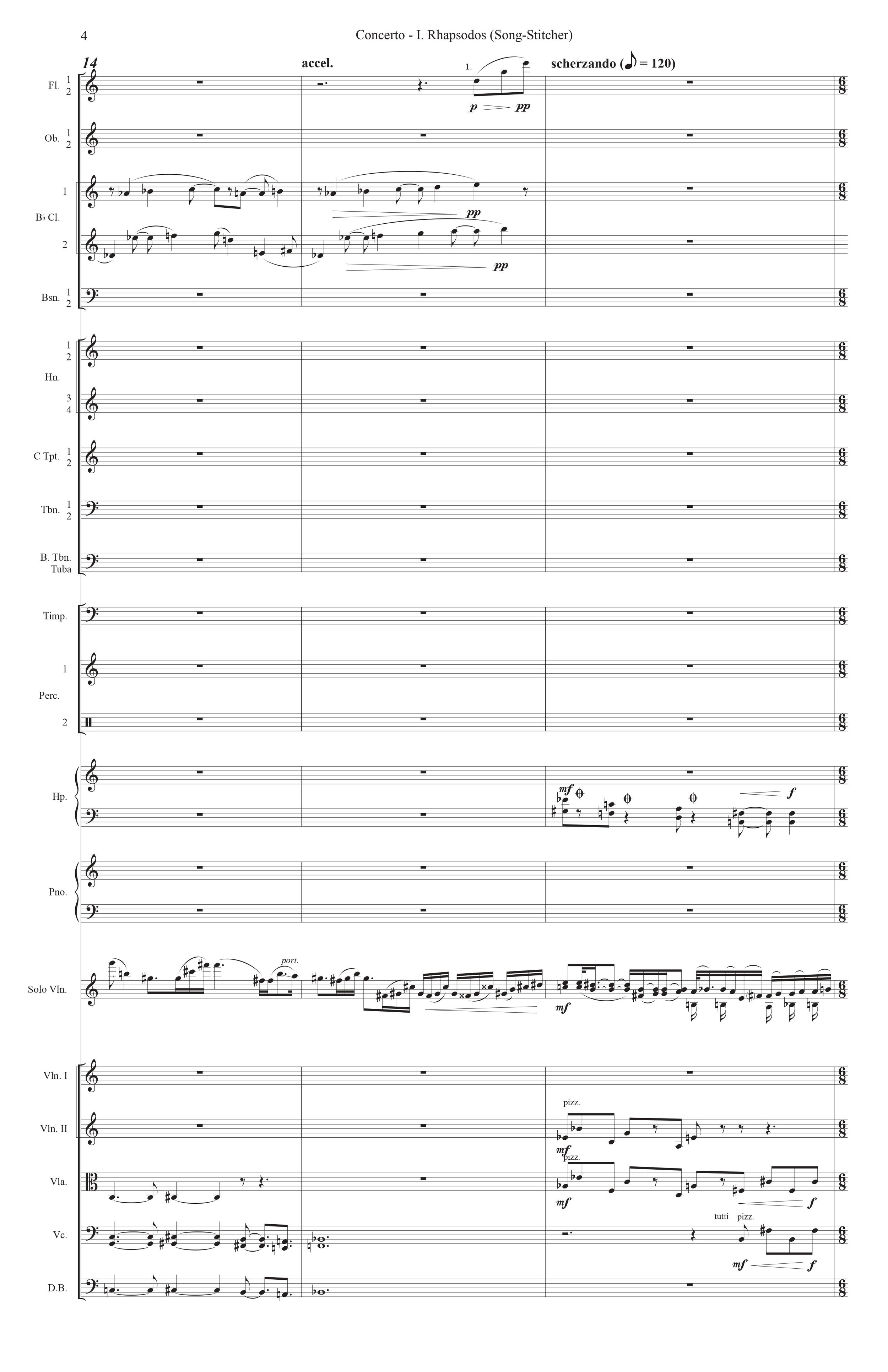

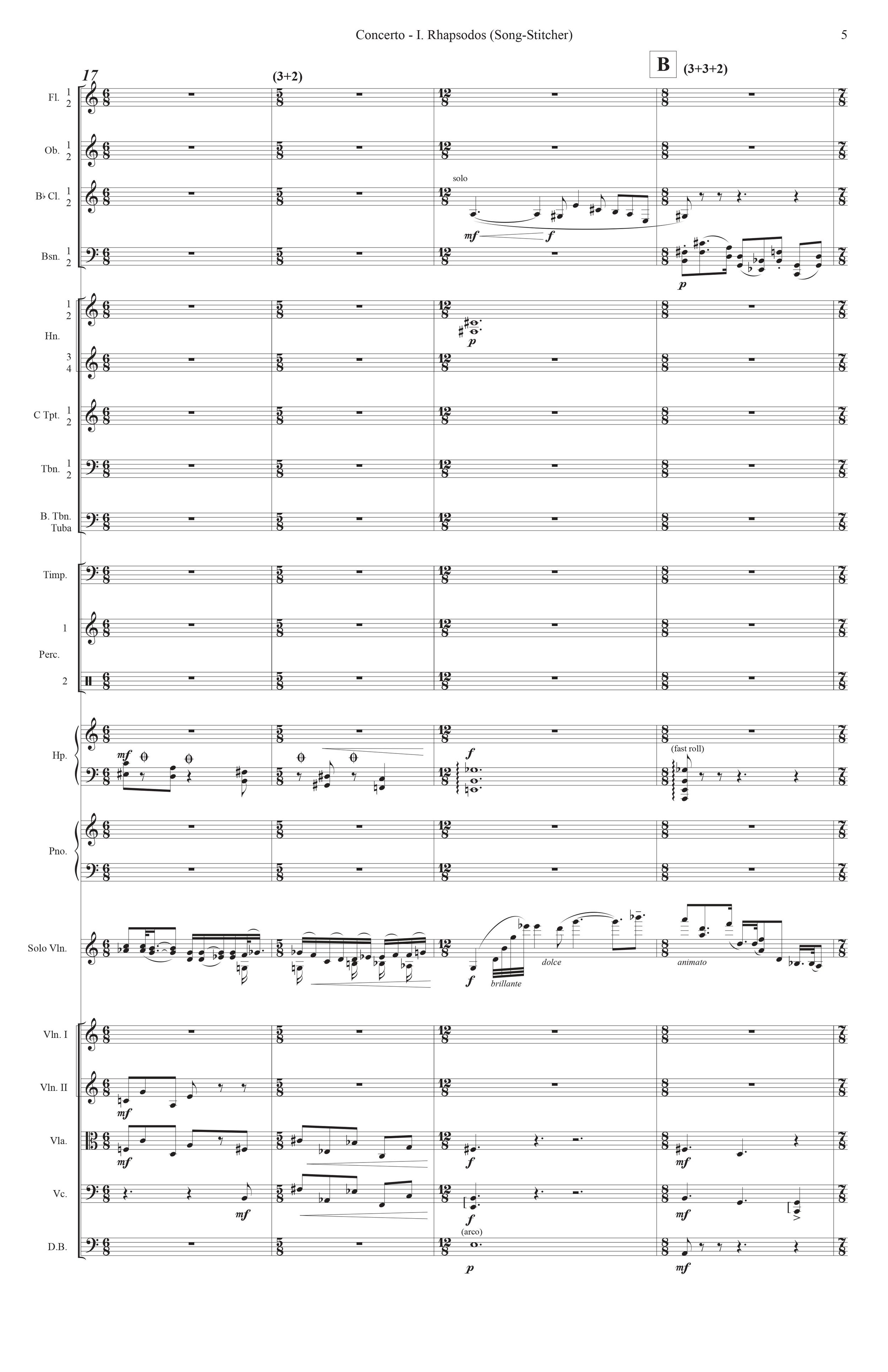

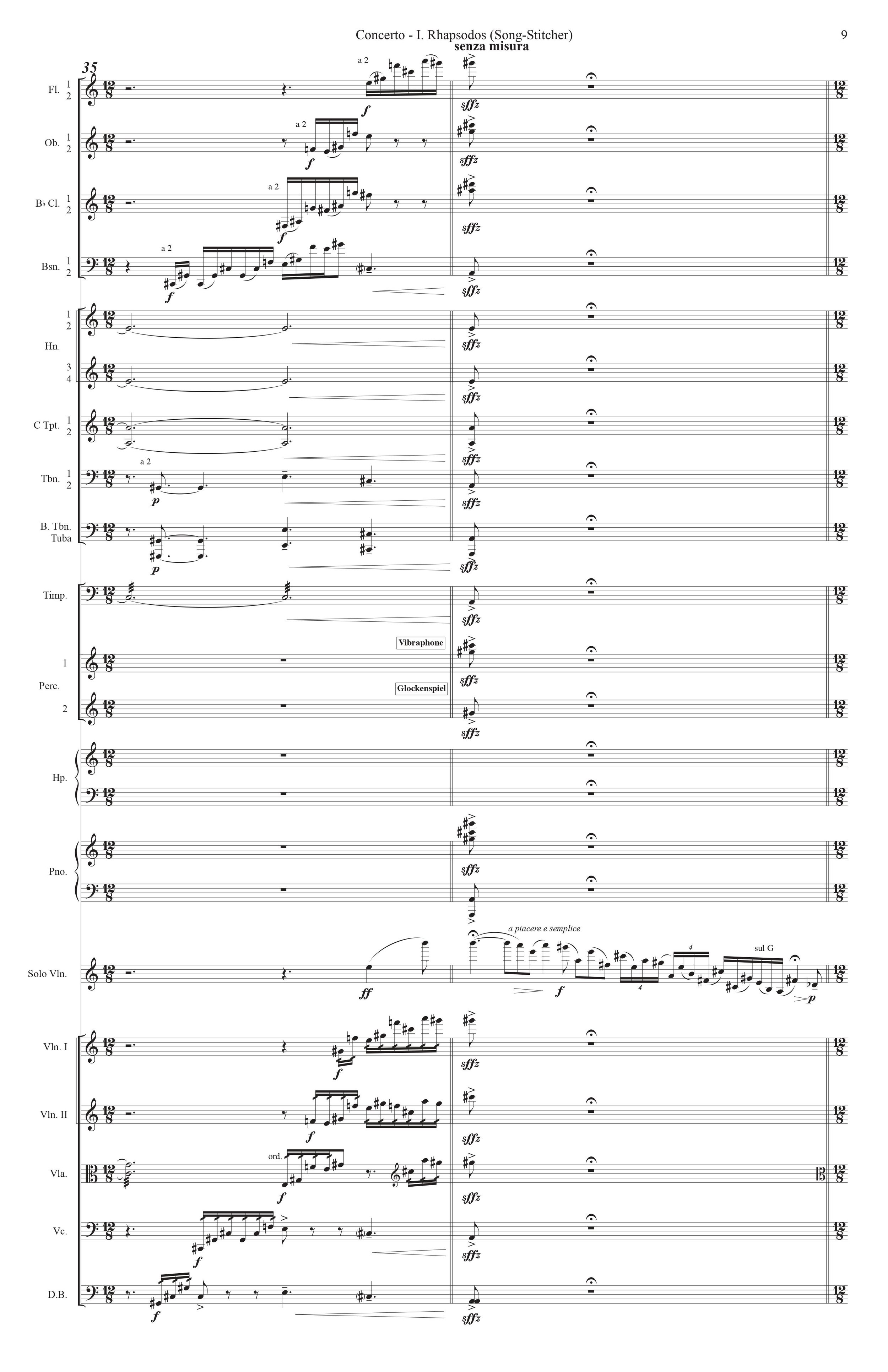

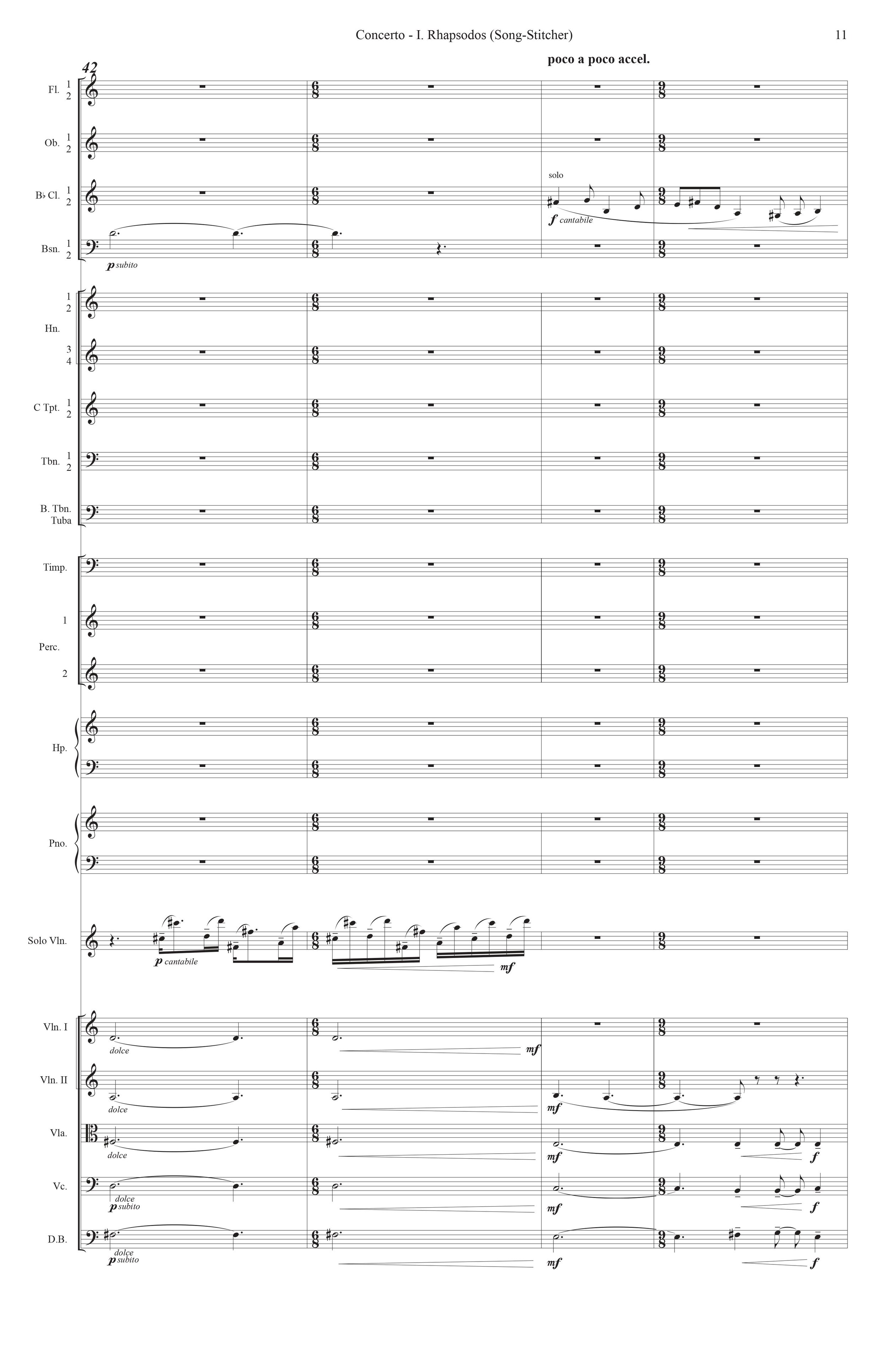

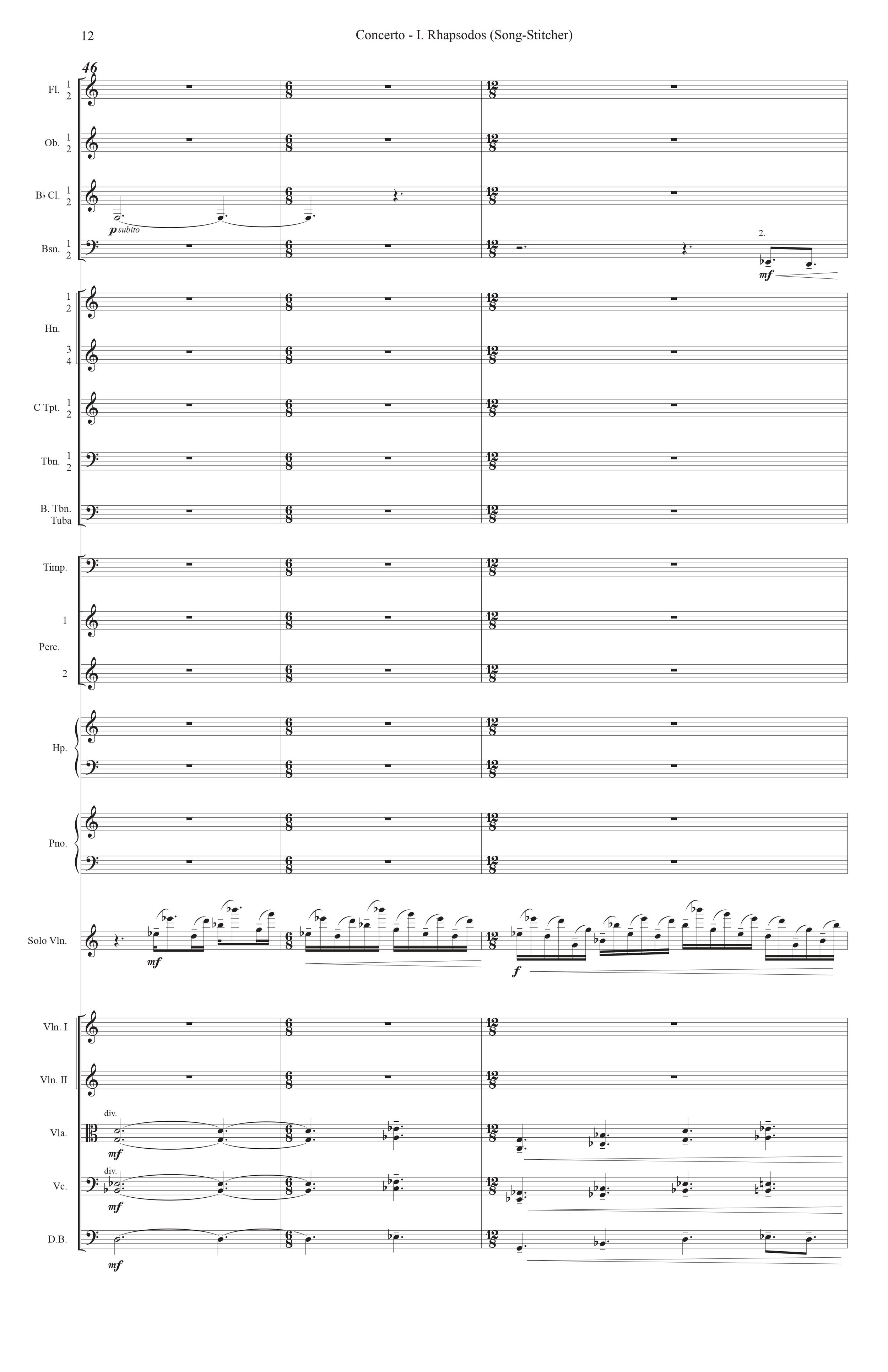

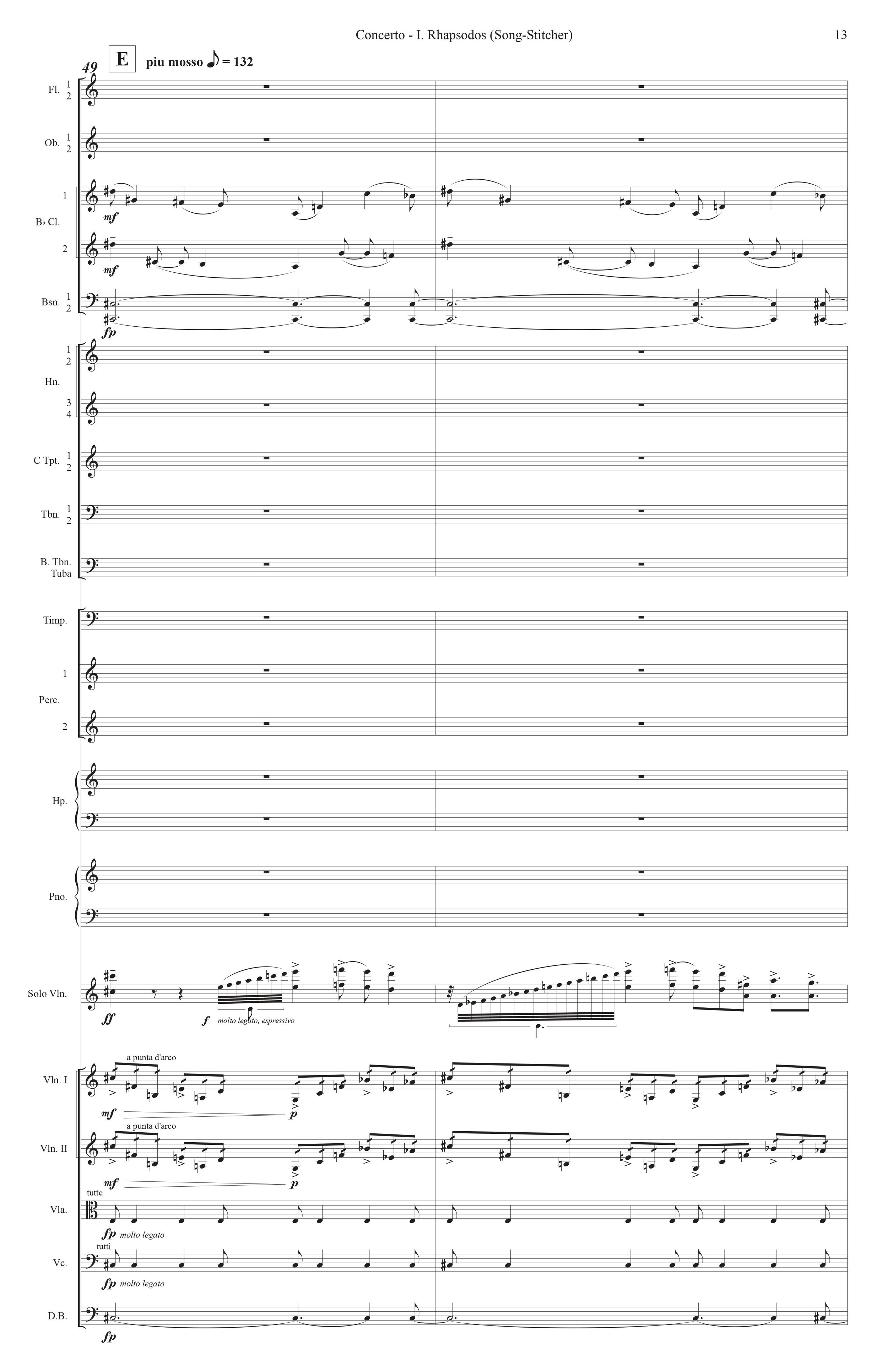

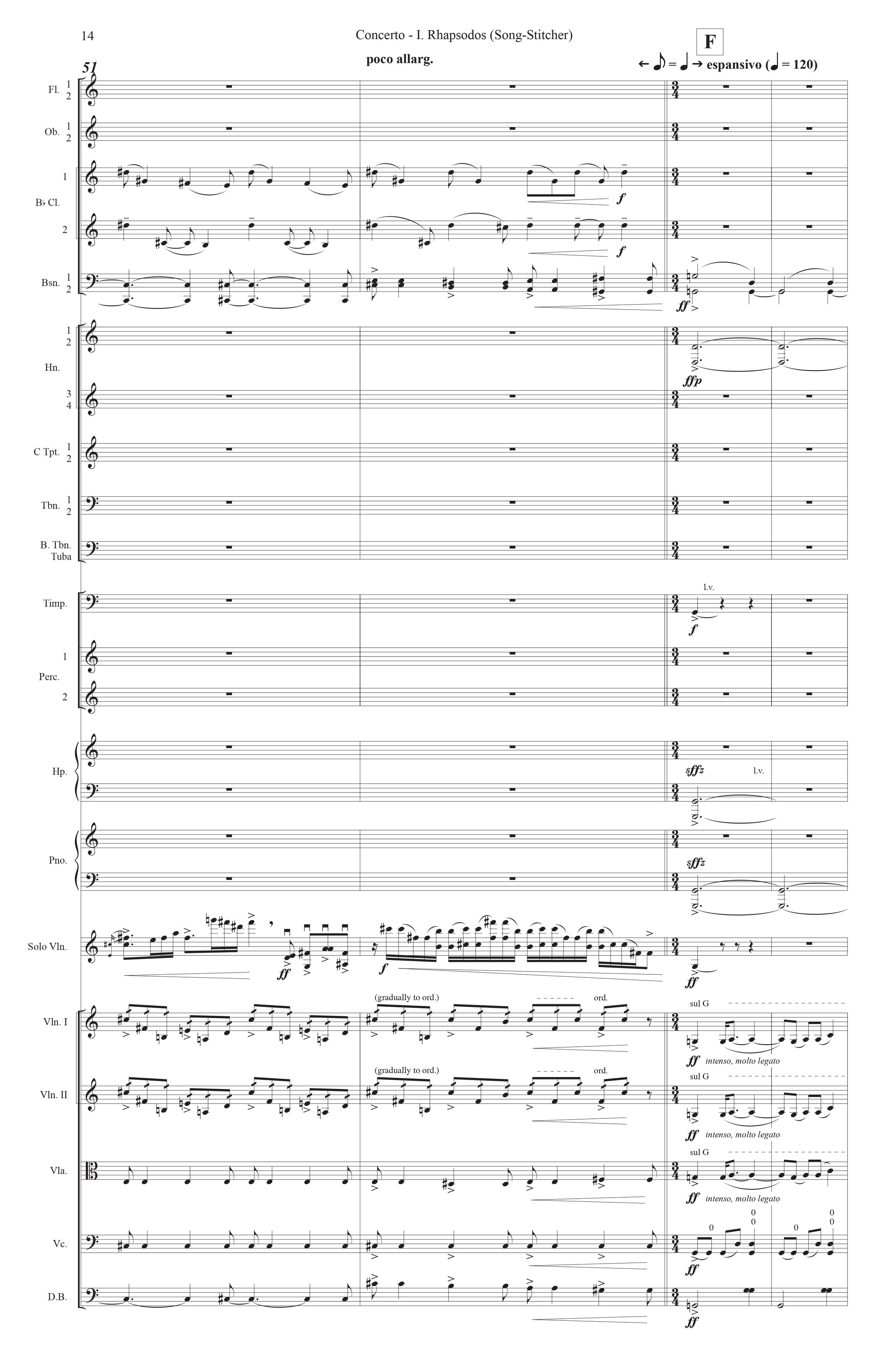

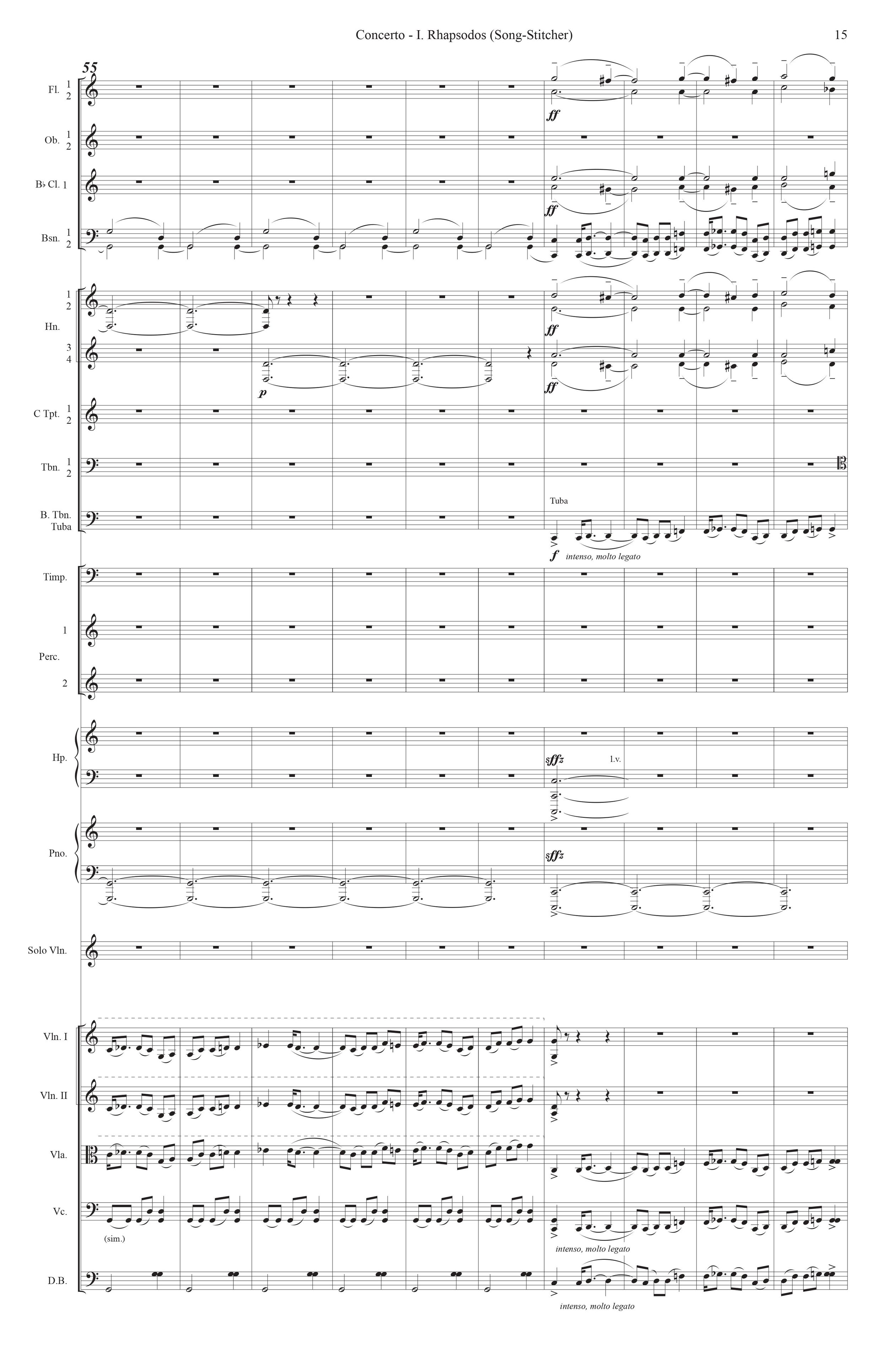

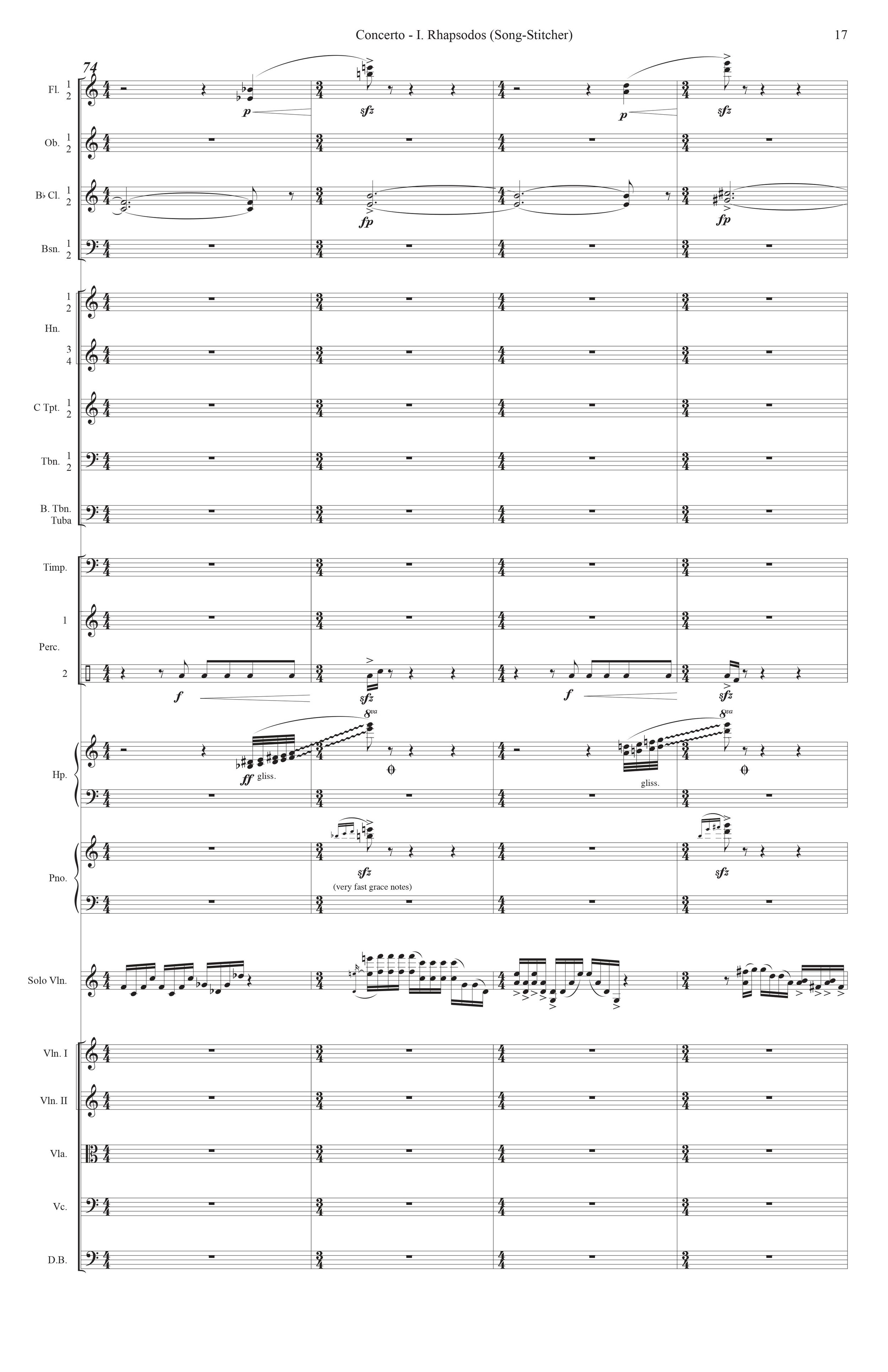

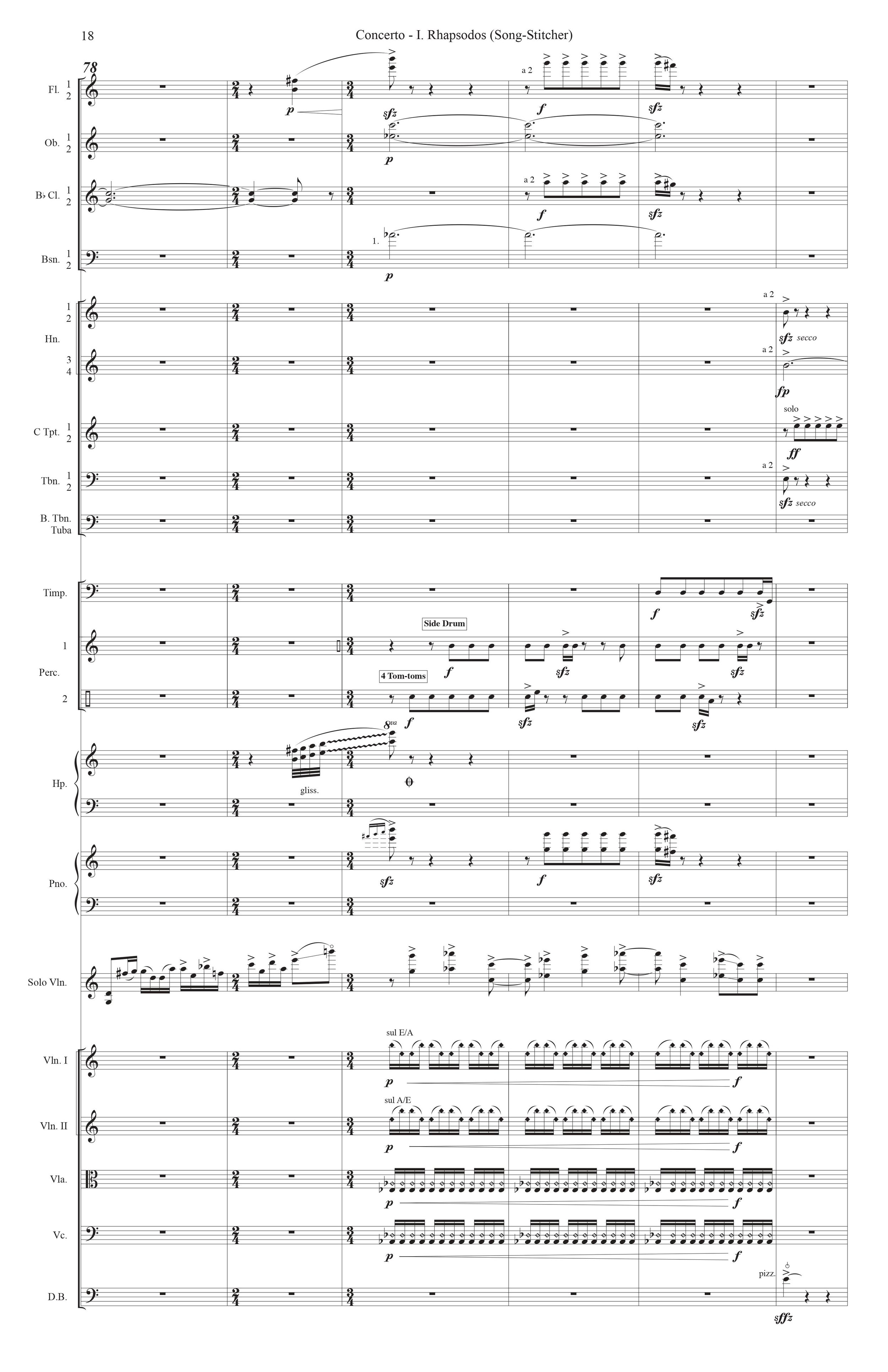

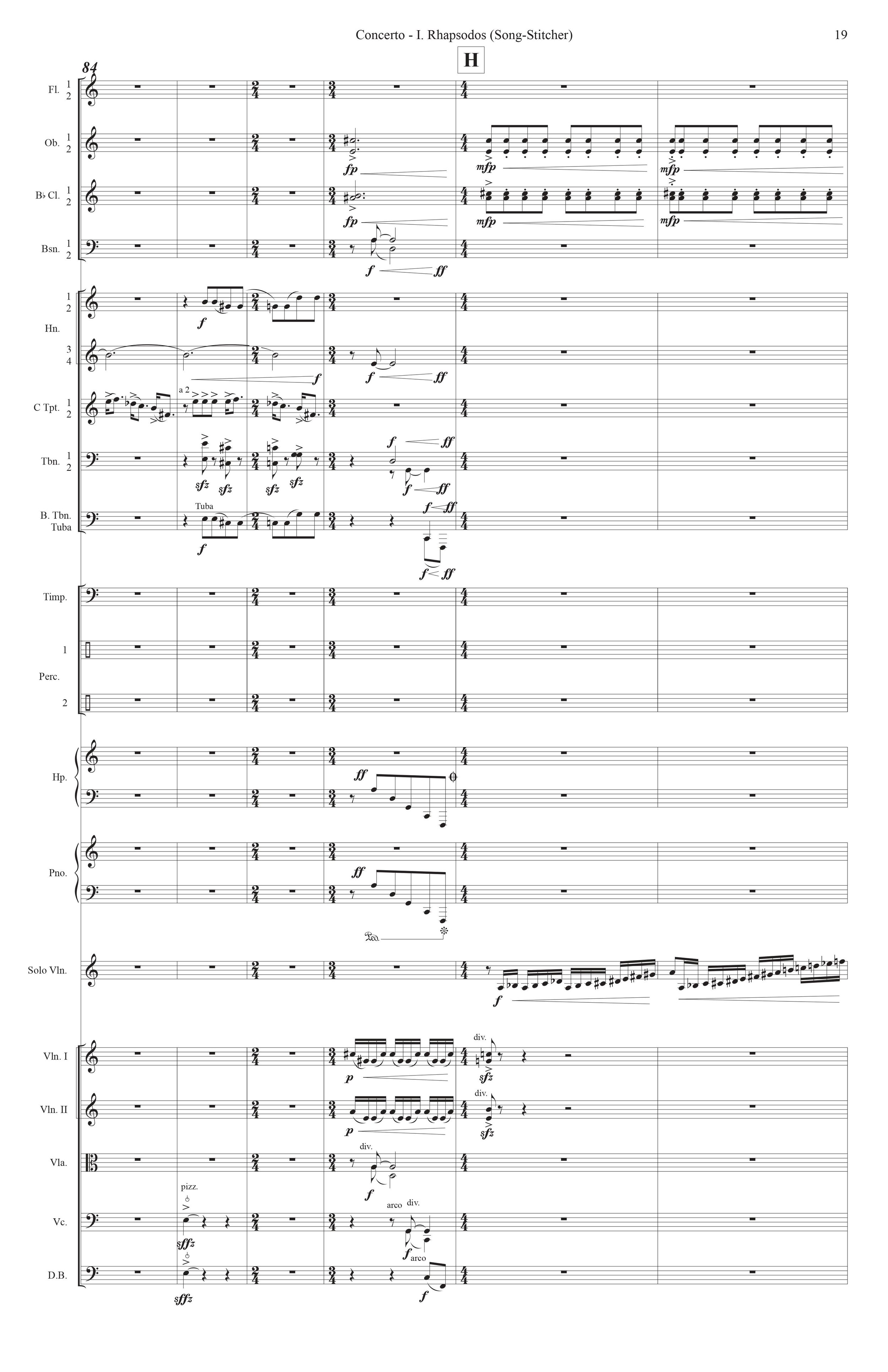

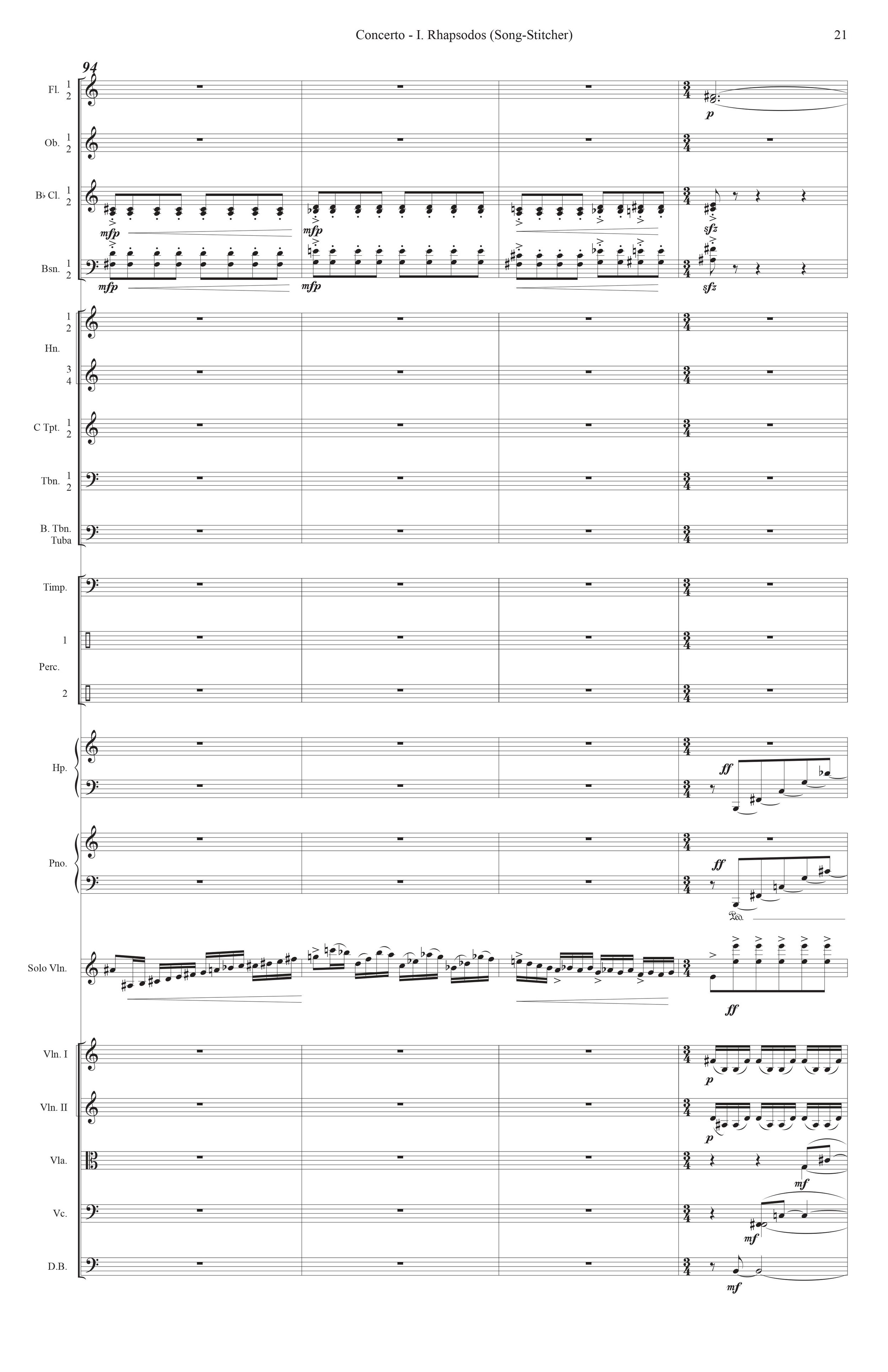

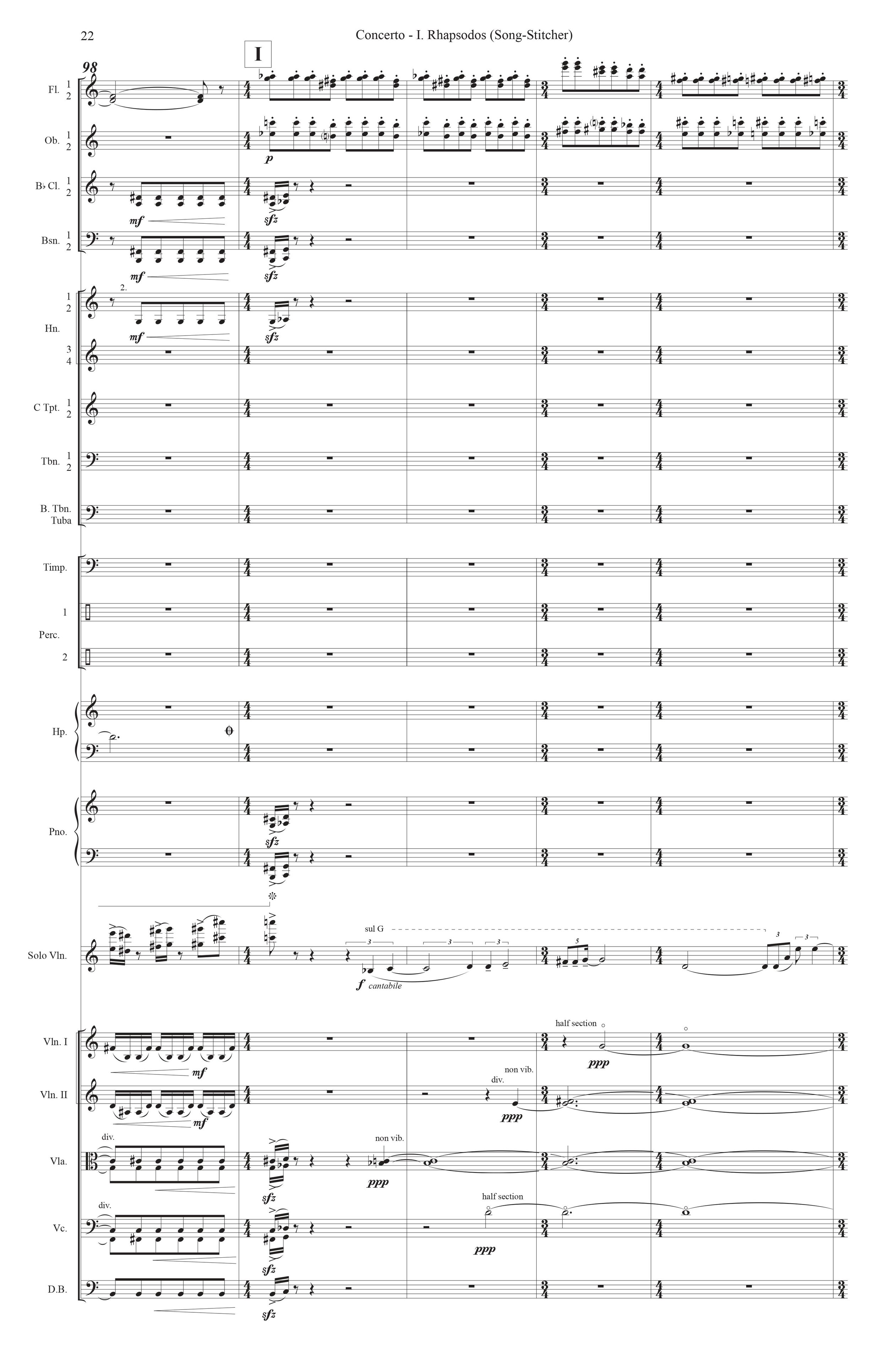

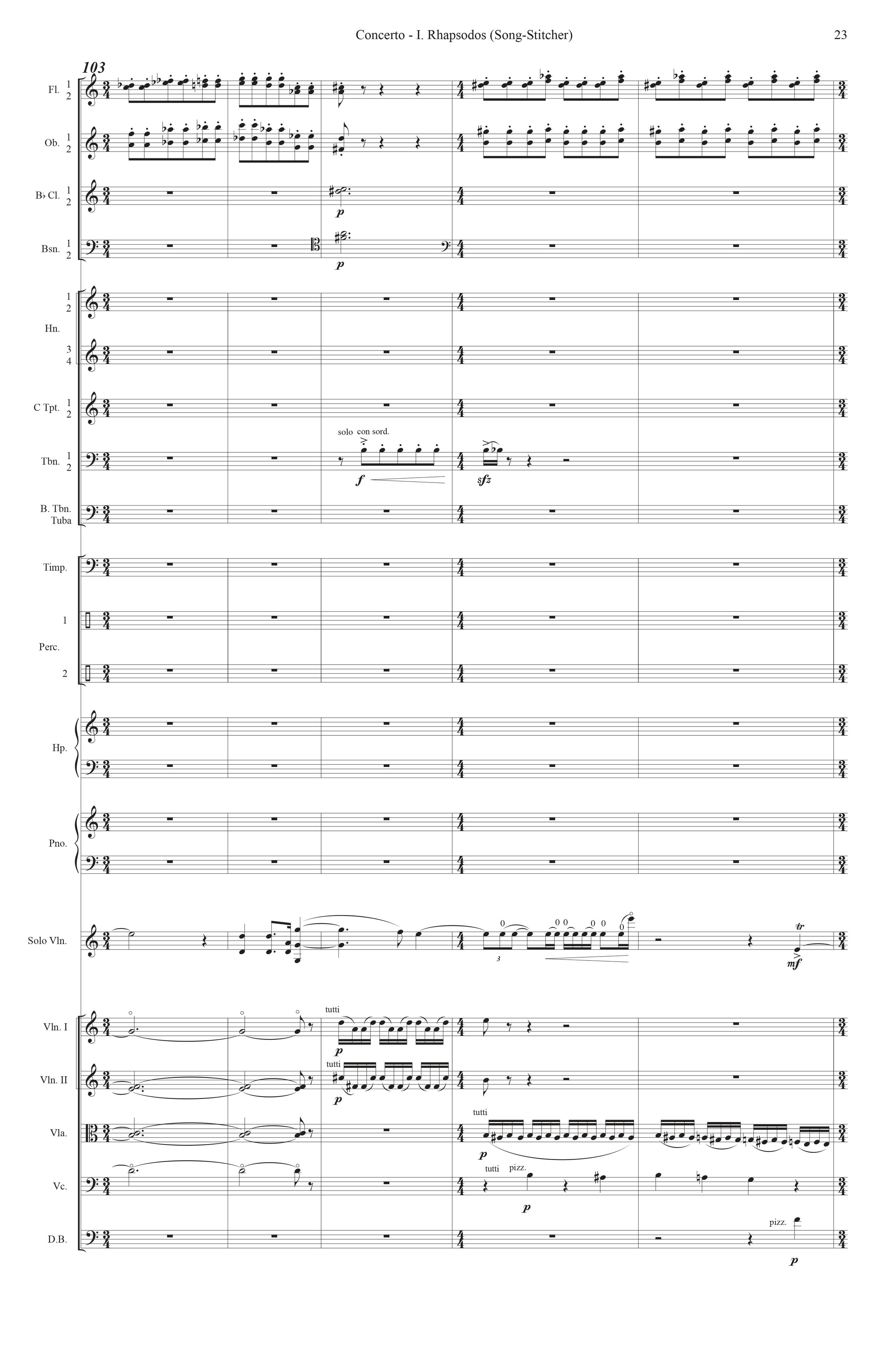

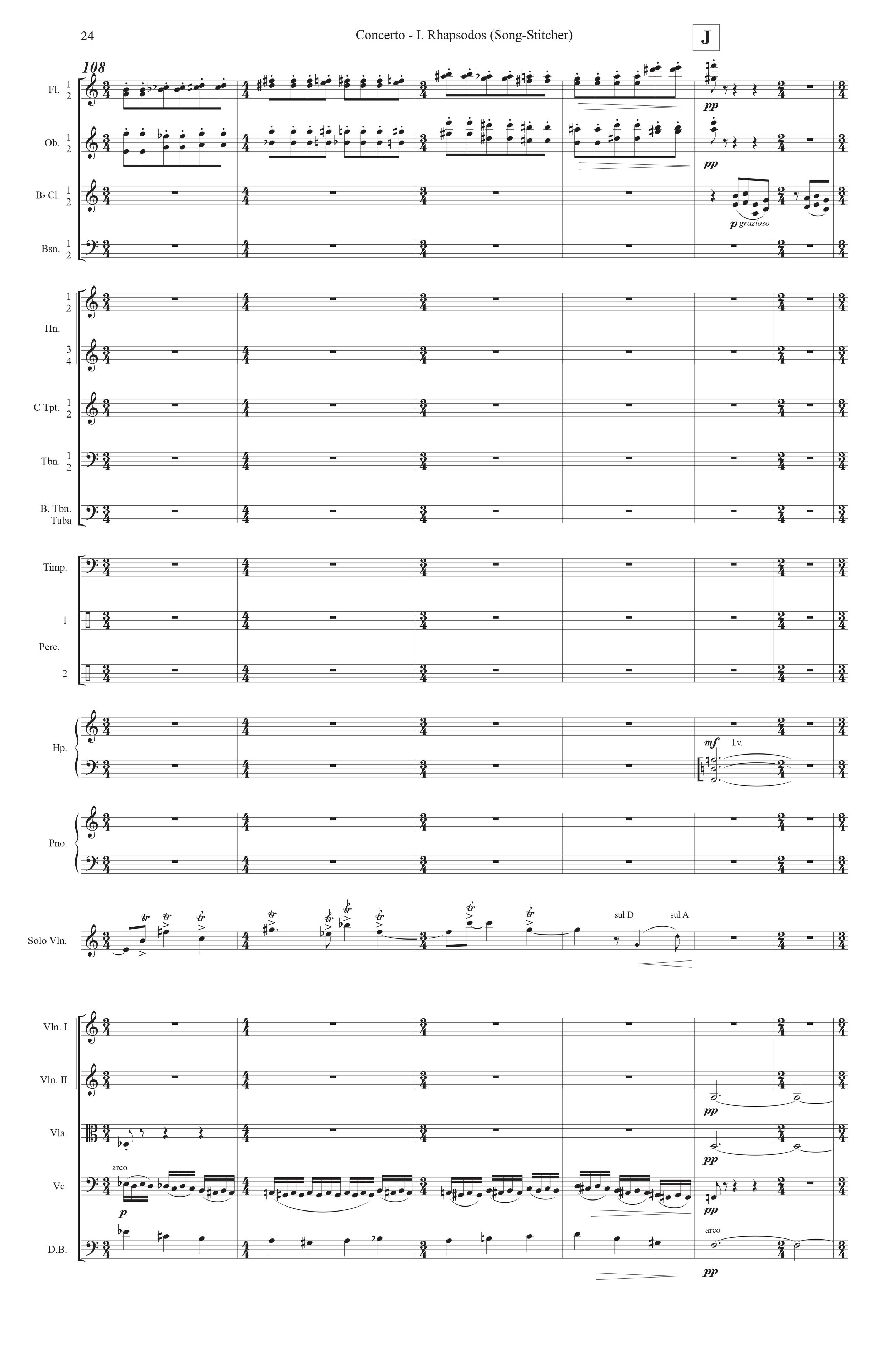

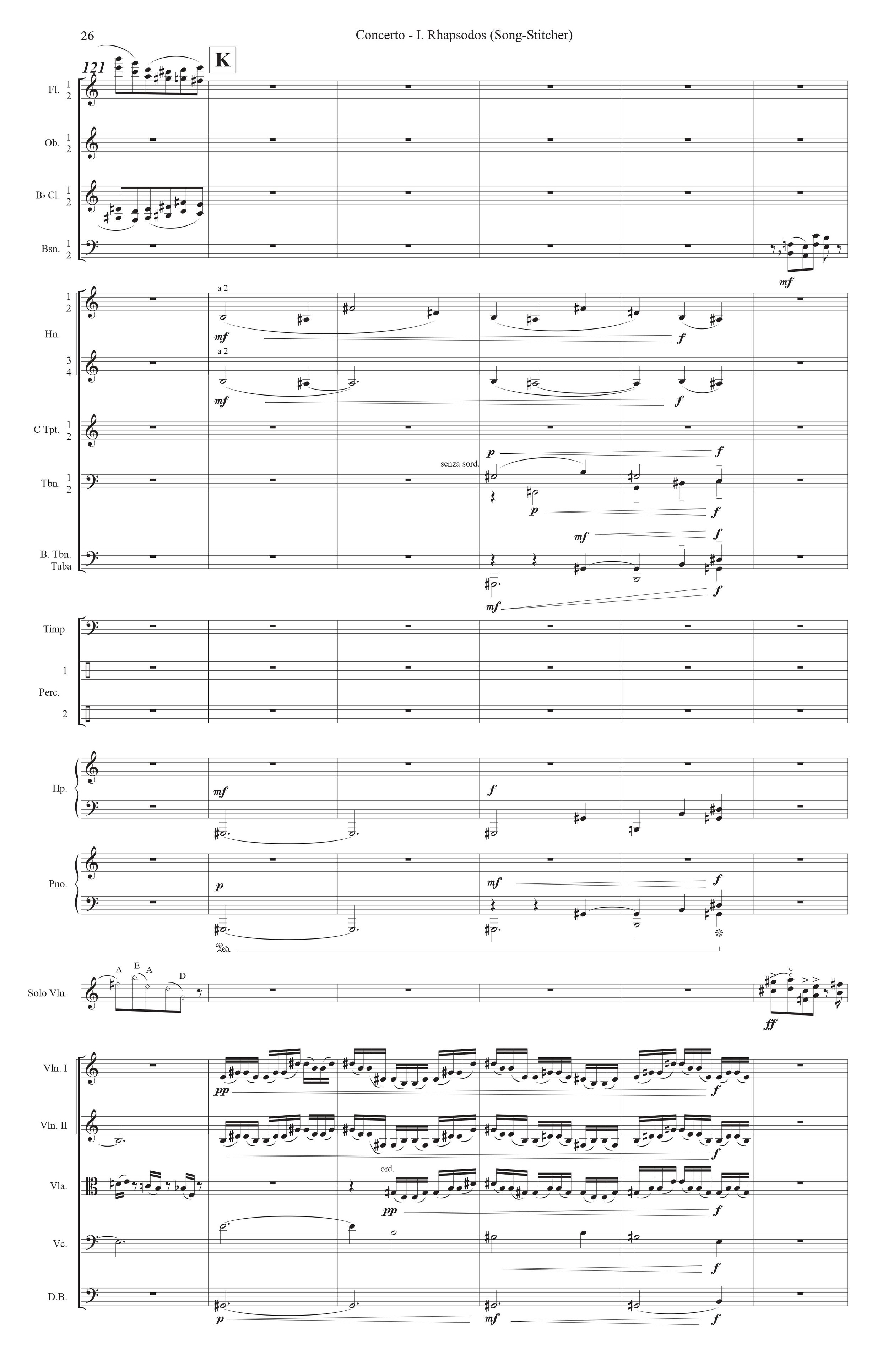

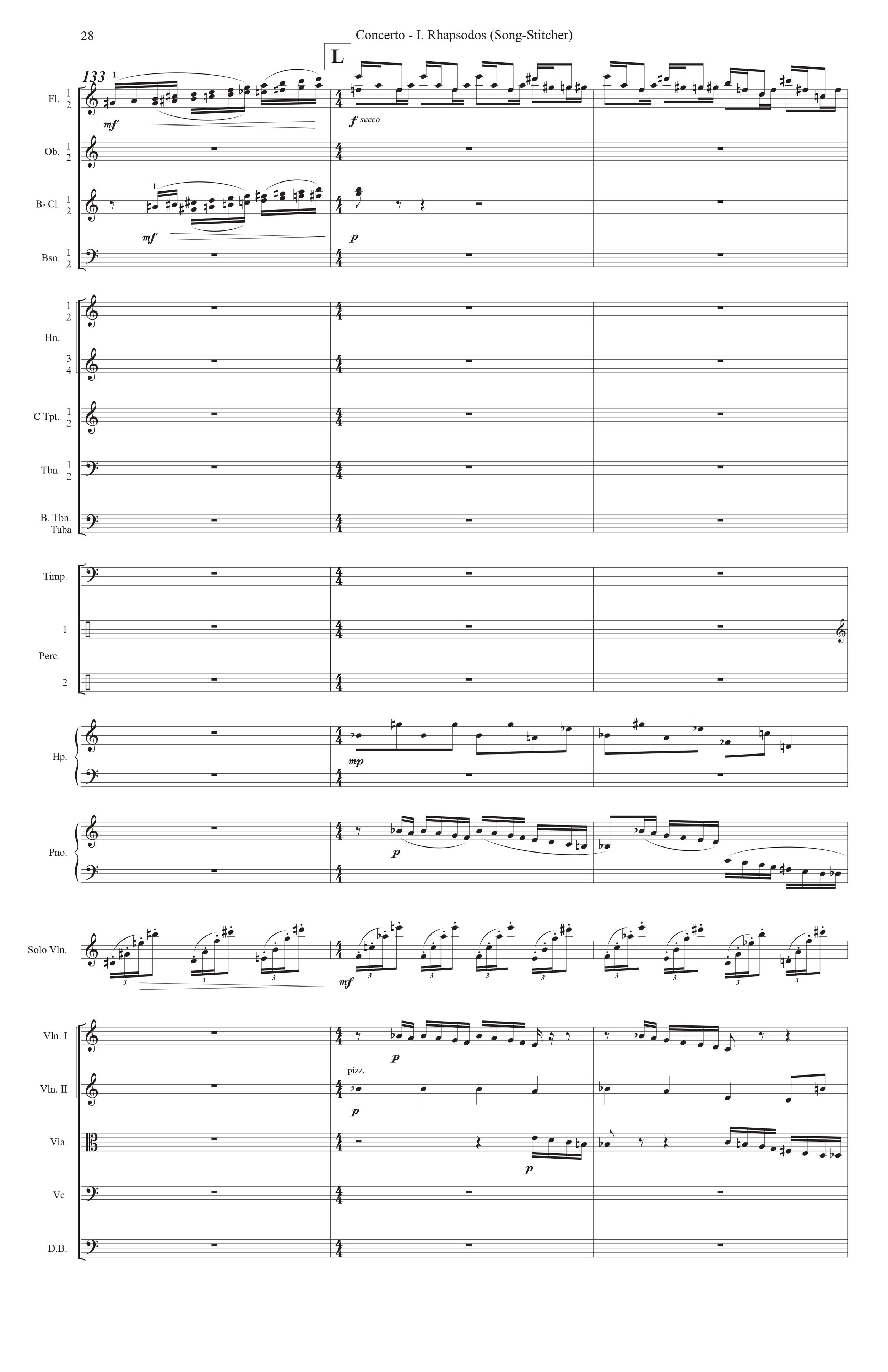

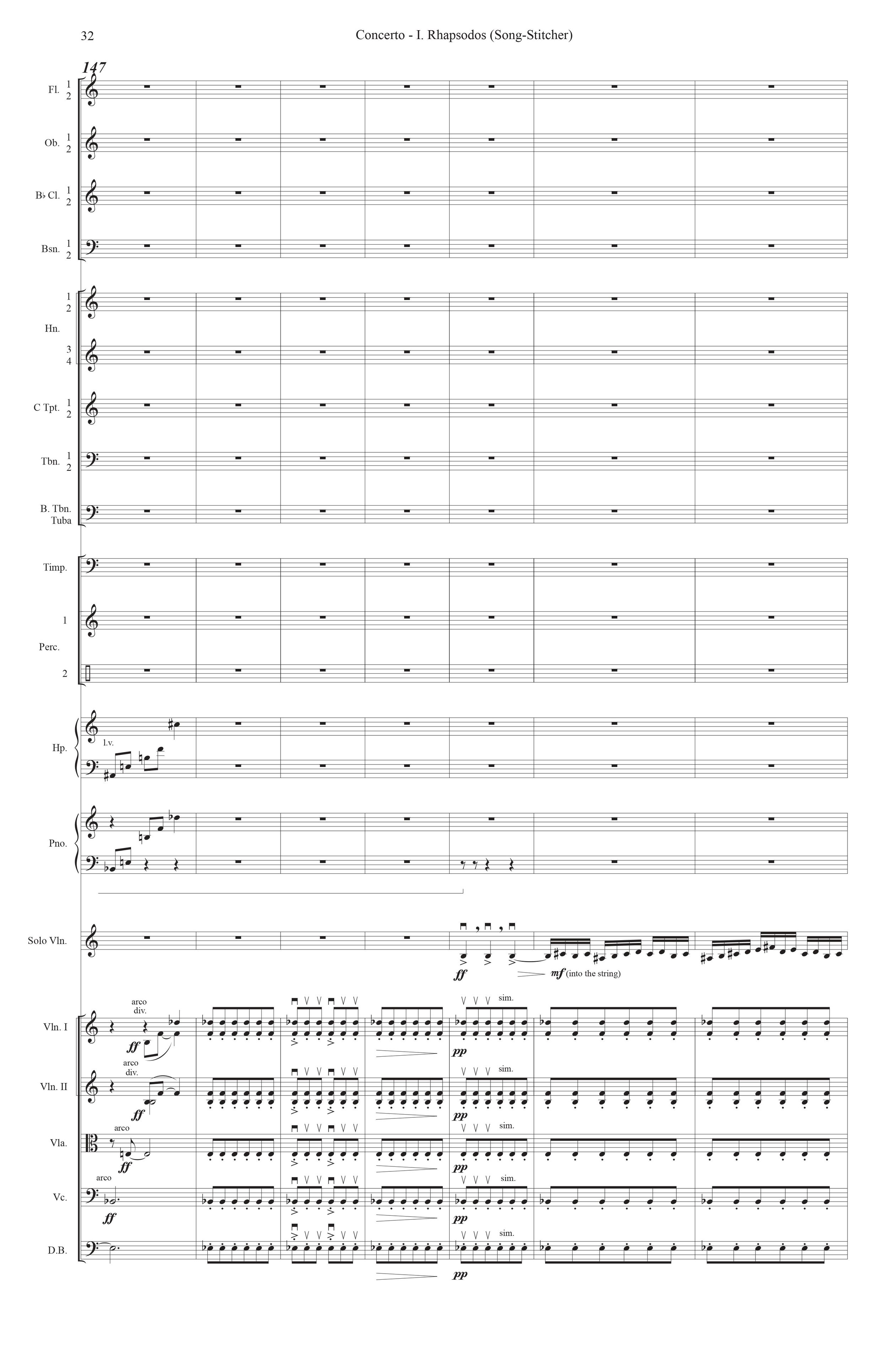

Concerto, for violin and orchestra (2021)

Duration: 24:00 minutes

Instrumentation: solo violin, 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes , 2 B-flat clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 C trumpets, 2 trombones, bass trombone, tuba, timpani, percussion (2 players), harp, piano, and strings

Premiere: December 2, 2022 by Jeffrey Multer, violin and The Florida Orchestra conducted by Michael Francis at The Straz Center, Tampa, FL

Notes:

There is something about a concerto, perhaps especially a violin concerto, that suggests a heroic narrative. The soloist is the protagonist of an imagined story, collaborating with or battling against the orchestra. As listeners, we identify with the individual persona at the center of the work, and follow their storyline with interest, delighting in their virtuosity and their ability to counterbalance or even overcome a massive orchestra through sheer force of will. When I began to think about writing my own concerto for violin, I was also thinking about ancient Greek epics and mythology, in particular Emily Wilson’s brilliant new translation of The Odyssey and Madeline Miller’s novels Song of Achilles and Circe. Miller’s novels are especially fascinating as they reimagine the well-known stories by focusing on secondary characters (Patroclus and Circe, respectively), rather than the typical hero (Achilles and Odysseus). Somehow, my immersion in Greek mythology, and thinking about heroic stories in general, made me see a potential path for my concerto: to simultaneously embrace epic storytelling, while also undermining it.

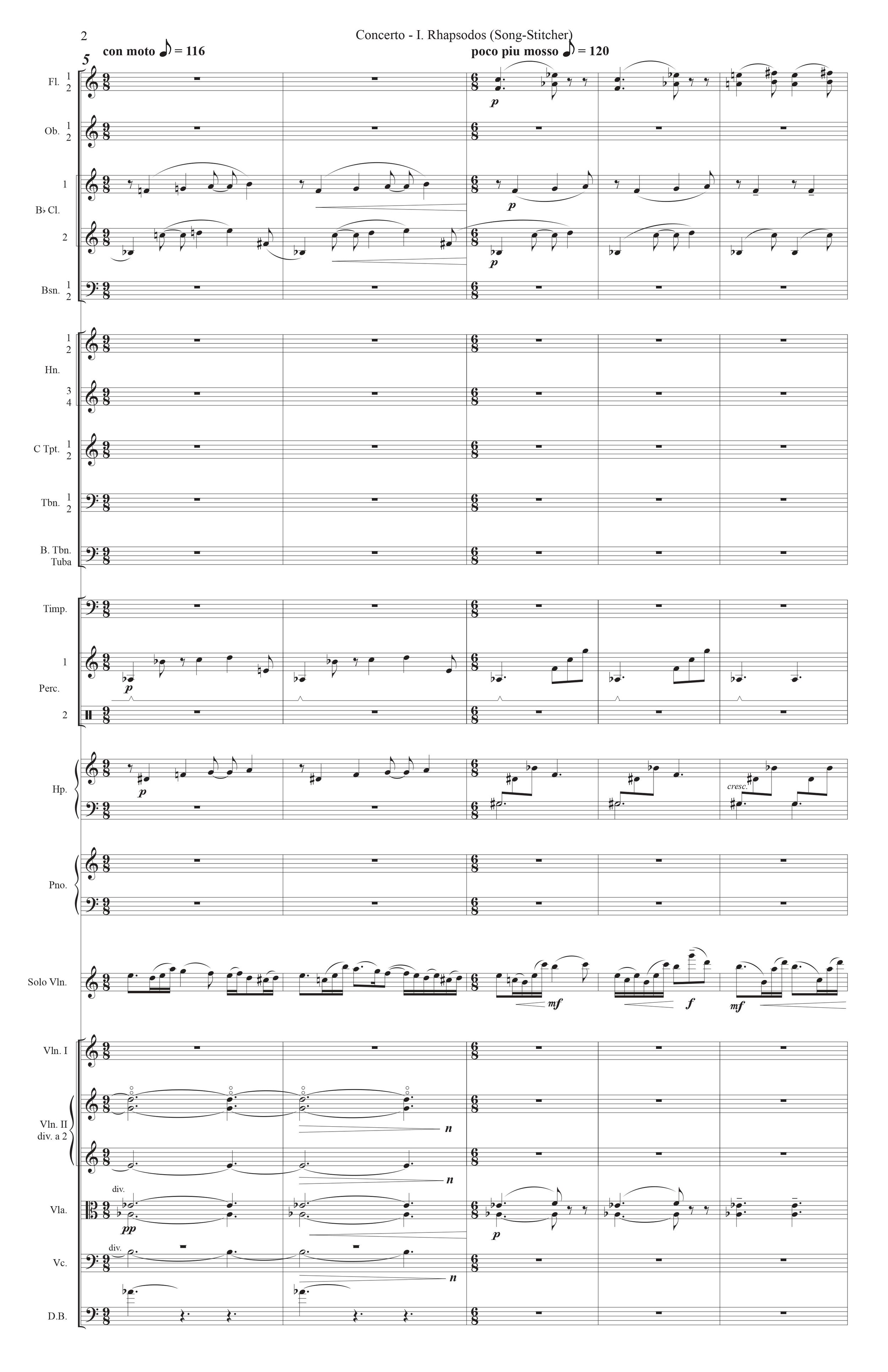

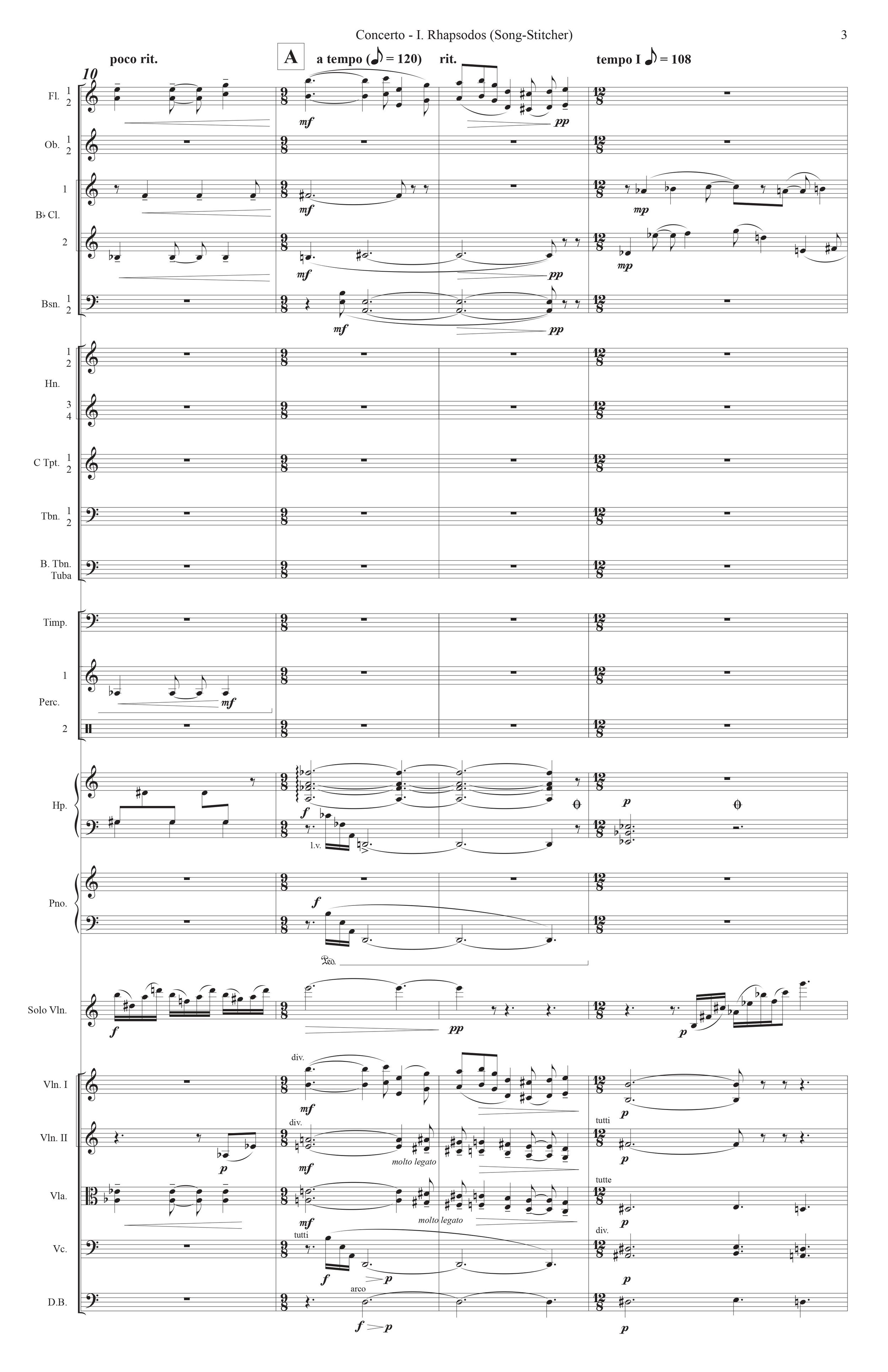

My concerto is in two parts. The first, titled Rhapsodos (Song-stitcher), is an epic told from the personal, hero- centered point of view. In ancient Greece, a reciter of epic poetry was called a rhapsode, the roots of the word literally meaning to “stitch together songs”. In this movement, the solo violin is the storyteller who embodies the hero, enchanting us with their triumphs and tragedies. The second movement, titled Moirai (Spin-Measure-Cut), refers to the fates, the three sister goddesses who determine the destinies of all mortals. In contrast to the heroic narrative, the Moirai would have a detached and impersonal attitude to any epic story; to them, there is no such thing as a triumph or tragedy, there is simply what is. The three sister’s names were often given as Clotho (the one who spins the thread of life), Lachesis (the one who measures each person’s allotment), and Atropos (literally the “unturnable” – the one who cuts the thread at the end of life). In this movement, the solo violin begins with Clotho’s music, evocative of spinning thread. The music of Lachesis is represented first with a passacaglia, a strict form, or way of measuring time. The spinning music returns before a massive fugue brings together all the themes from the concerto, another strict form that “measures” the protagonist’s life. In the final moments, the soloist attempts to defy fate, before the final snip of Atropos’ scissors. “Comes the blind Fury with th' abhorred shears, / And slits the thin- spun life.”